whistlestop caboose

The view from the back.

About Me

- Name: whistlestop caboose

www.zidao.com Apprentice harmonizer, for sheer fun. Journeywoman writer, for work and pleasure. Starting point was Iowa, current stopping point on this journey is Switzerland, with frequent pauses around the world to watch and listen to the crowd, and occasionally make comments.

www.flickr.com

|

Wednesday, November 30, 2005

Tuesday, November 29, 2005

cafe au lait, now ecru refined

ecru label on Swiss white chocolate

ecru scarf against colored scarves

ecru scarf against colored scarves

the ecru scarf, solo

the ecru scarf, solo

the ecru scarf and ecru bowl holding ecru white chocolate powder

the ecru scarf and ecru bowl holding ecru white chocolate powder

the ecru scarf, chocolate and ceramic bowl, a closer look

the ecru scarf, chocolate and ceramic bowl, a closer look

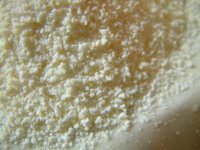

down to the basics: white chocolate, really ecru in color; powder close-up

Light. The eye's perception of color. Texture. Color is endlessly elusive. What earlier today looked like cafe au lait now looks more like ecru. And ecru solo appears to be different from ecru against color.

Color of the day: cafe au lait

The most enigmatic color of all must be one that I can never name - beige? tan? cream? pale brown? Tomorrow, more on the sources of color's names, but for now let me share a fun discovey, Pantone's chameleon, to help you solve your color problems. I love Pantone's color swatch books, and I envy the professional designers who treat them the way I do my kitchen spices. A bit of this and a dash of that and it all comes out right.

The most enigmatic color of all must be one that I can never name - beige? tan? cream? pale brown? Tomorrow, more on the sources of color's names, but for now let me share a fun discovey, Pantone's chameleon, to help you solve your color problems. I love Pantone's color swatch books, and I envy the professional designers who treat them the way I do my kitchen spices. A bit of this and a dash of that and it all comes out right.

How to change a battle into a chocolate pot

Switzerland is famous for its peaceful neutrality and its chocolate. Geneva, for much of the year, claims to be a center for banking and international organizations, but for the past 400 years, every December, it has devoted two weeks to reminding people that civic unrest can be profitably turned into chocolate pots.

The chocolate pot lesson is called L'Escalade. In 1604 the Duke of Savoy attacked Geneva. As they scaled the walls Mother Royaume, surely one of the town's stronger citizens, tipped her cauldron of boiling soup over the Savoyards heads. Geneva was saved and in gratitude, invented the chocolate cauldron, eaten in large quantities by the citizenry every year. Fittingly, UBS, the country's largest bank, and Migros, one of its two big supermarket chains are among the sponsors for events surrounding the Escalade celebrations.

Yesterday I shopped at the Migros, where I was confronted by a ceiling high stack of chocolate marmites, or cauldrons. I bought one of the filled ones, but we will have to wait until December 10, the day of Geneva's Escalade celebrations, to find out what is inside. You can also buy empty ones, to fill with your own chocolate or marzipan treats.

Here is what my inexpensive one looks like from the outside. Next week when I am in Geneva I will visit a chocolate shop to buy a handmade one.

Monday, November 28, 2005

My Swiss garden: Celery stalker

Rosemary's last stand

Rosemary's last stand Winter comes to the garden

Death will come knocking one day and I imagine it will be much like the first day of winter, the one where frost and ice and snow lean on the door and refuse to go away. This is the day when the list of garden chores is crumpled and dropped to the floor: no point in putting in the bulbs now or trying to get down that last bit of mulch or prune the roses. Planning is a thing of the past.

It tends to be a time for reassessment, much like the pre-confessional moment called the examination of conscience I learned as a Catholic child. You tote up your good points and jot down your weak ones and failings, and hope to be forgiven that the second list is invariably longer than the first.

Death gives us practice sessions. By the time I am a master gardener I will be ready to face that final winter, I expect.

The Celery Problem

My Swiss garden was created from old mountain cow pasture land. The first two years were devoted to lifting stones and winning tugs of war with plants that had roots as long as yodel echoes. We planted potatoes, tomatoes and lettuce. Braver the next year, we tried all the other vegetables and herbs that marry the outdoor garden and the indoor kitchen. Among these was celery, planted the summer of 2004 for the first time. To be honest, I had never seen a growing celery plant, and if the leaves did not look much like the supermarket ones, I was sure the plants would give great flavor.

To blanch or not to blanch

My mother-in-law visited from Kent, in England, and as we surveyed the limp, spindley late summer plants she said that when she was young they blanched their celery. This involved digging trenches and planting the celery low, then heaping dirt up the sides, to keep it sweet and light colored. We then looked up blanching in the Royal Horitucltural Society's Encyclopedia of Gardening and discovered this is no longer done. It kills many of the vitamins and newer varieties do not need it. Over the summer the celery grew, but barely. We cut one or two branches and used them in soup. The crop was not a success.

I vowed to do better by celery in 2005. I bought healthy plants and they were still alive and happy a week later. I watered the vegetable slope generously and it was a good summer for rain. I reread the gardening books and learned that the stalks would be sweeter if I heaped hay around them. I watched and waited.

Celery, I have learned, does not grow quickly. Apparently, it can get bugs, but we had none. I nipped off a leave now and again, a branch or two that tasted fine, although they were very slim. We waited and waited, with great hope. But a mountain garden can grow very slowly, and our corn was ready only at the start of November. The celery would clearly fatten up only in time for the Thanksgiving feast at the end of November.

The day before winter's first cold blast, I despaired of waiting longer and I dug up the six plants. I read the instructions - dig them up, long roots and all, then cut off the roots and you will find they keep well for six weeks in a cool, humid place. My hands were icy and I skipped the cut-the-roots-off detail. I placed the greens in a crate in the laundry room which is cool and damp. They still did not look like the supermarket variety, but they had a certain upright beauty.

The failed gardener

Split peas soaking in a Nicholas Mosse bowl

Split peas soaking in a Nicholas Mosse bowl

I used one plant in chicken stock, some of which then went into yellow split pea soup, American style, enjoyed by all. I had so much celery that I added more to the unused stock, thinking to make celery soup, without first taking time to find a recipe. Ouf! as we say in French, not a nice taste. So all the weekend leftovers, which consisted of baked apple and pork and hot peppers and sweet chili sauce and so on, went into the broth. Daughter Tara, suffering from flu, refused to eat until she tasted the magic soup which I called "celery and then some" and by the time she had a second bowl the rest of the family was devouring it.

Facts about celery

The summer of 2006 will provide a wonderful crop of Swiss alpine celery, I have promised myself. I am starting early, by turning now to the professionals who tell me these facts about Apium graveolens:

- Homer probably ate it and he included it in The Odyssey (selinum)

- The French or Italians were the first to use the word celeri, in a poem - this from Texas A&M University's horticulture department

- you should plant them seven inches apart / you should plant them 12 inches apart (from two books, confusing advice)

- you must be sure to heap manure around them when you plant them and they are happiest in "fertile muck", says the University of North Carolina

And, I've noted for further investigation in 2006, the people in North Carolina say that more than 5 days at 40 degrees, presumably fahrenheit, will cause bolting, thereby ruining the crop. But who is bolting, the gardener or the celery?

If the celery does not bolt

A more experienced gardener will probably not assume that the celery is running away from home.

In California, some people have a wealth of celery experience. Steve Bottorff, a garden tools expert, startled me when he explained that celery harvesters spend up to an hour sharpening their new knives and they use every break every day to resharpen them. His photos of the celery harvest in Salinas, California, are enlightening.

Imagine a celery harvest big enough to cut!

Friday, November 25, 2005

Thursday, November 24, 2005

Wednesday, November 23, 2005

Infinity, the Thanksgiving guest

Infinity: I intend to give thanks for it this Thursday. Let me put forward some arguments for why it deserves our gratitude.

Infinity, in its everlasting reach forward and outward, ironically takes me backwards. I remember standing on a road with my father the engineer, who sold the bulldozers that built the Interstate, a fact of which I was immensely proud. Thanks to my family, America would be tied together by one long ribbon. But, you have to imagine most of it, my father said, pointing me at the horizon. Do you see where the road ends? I nodded. Anyone could. Well, he said, it doesn’t end there. But you can train your mind to see beyond that point.

This is one of the most redeeming things about the human race: our ability to imagine things beyond the point where we can measure them. My son has been struggling to write an essay for school on knowledge, and he concluded, like so many before him, that we cannot know anything for certain. It’s easy to see this as negative, but it is really about infinity: just beyond that point at which we think we know something, lies the unknown, and we keep striving for it. Good for us!

I grew up in Iowa. The last Thanksgiving dinner I had in the United States was 26 years ago. It was always my favourite holiday, partly because I loved the trappings and the food and the ambience, and in part because it seemed to me to be the truest American holiday, the one everyone could celebrate. We were all born potentially festive and thankful, though some unfortunate people end up grumpy and disgruntled. I left Iowa, then the Midwest, then the U.S. The first few years away, I missed family and friends sorely on that last Thursday in November, which was always an inconvenient time to go home. I went to great lengths to find turkeys in France, where they had to be ordered two weeks ahead in order to fatten them up properly. This was surprising news to someone who grew up on Butterball turkeys with their red buttons that popped out when they were done.

I left Iowa, then the Midwest, then the U.S. The first few years away, I missed family and friends sorely on that last Thursday in November, which was always an inconvenient time to go home. I went to great lengths to find turkeys in France, where they had to be ordered two weeks ahead in order to fatten them up properly. This was surprising news to someone who grew up on Butterball turkeys with their red buttons that popped out when they were done.

I remembered with great nostalgia the Thanksgivings of my childhood (search this blog: Pilgrim corn).

Two attempts at feasting in France on Thanksgiving Day proved rough: there was no hope of taking the day off to cook, the meal was started late and lasted long, and Friday was a work day. Even the French would not forgive missing work for a case of over-indulgence at the table.

I shifted the celebration to the weekend after the big day. When my children were little we put paper turkey name cards around the table and I had turkey candles shipped over from America, as we now called it. With no one else celebrating, it seemed a bit forced. Gradually, the weekend fetes faded away.

I don’t miss it because I have started my own celebration. It consists of pausing on Thanksgiving Day long enough to find one thing in the universe that has given me enormous pleasure over the years. I then do a bit of research and I think about it. I feast on it.

Last year it was clouds, prompted by the sudden recollection of vertical stacks of the white stuff that our airplane skimmed over just as we arrived in Zimbabwe on my first flight to Africa 20 years ago. I thought that in a country with such skittish politics today the only unchanging thing might be the clouds.

Sitting in Switzerland, I pointed my camera to the skies, reread weather lessons I must have known at the age of 12, looked at the clouds in my parents’ retirement hobby paintings and remembered them discussing what a challenge it is to paint these well. And I made the delightful discovery of England’s online cloudman.

Sitting in Switzerland, I pointed my camera to the skies, reread weather lessons I must have known at the age of 12, looked at the clouds in my parents’ retirement hobby paintings and remembered them discussing what a challenge it is to paint these well. And I made the delightful discovery of England’s online cloudman.

So this year I will give thanks for infinity, not to be confused with The Infinite, which is a more religious notion.

One thing I love about infinity, defined very loosely as that which goes on and on, is that it is both beautiful and useful. I can dream about the vanishing point in art and I can argue about the mathematics of it, or more likely, traipse through other people’s learned efforts to do so. That will be my research. A green field with the rows neatly planted leads not to the end of the field but straight into the blue November sky. What magic! I suddenly remembered today the first short story I wrote, not a very good one, but the teacher praised the imagination behind it, and that was enough to spark a writing career. It had little plot, but much color in its description of a road that never ends, that keeps pulling us along.

I suddenly remembered today the first short story I wrote, not a very good one, but the teacher praised the imagination behind it, and that was enough to spark a writing career. It had little plot, but much color in its description of a road that never ends, that keeps pulling us along.

We can be philosophical about infinity and we can also just plain enjoy jousting with it, as my mother did in a painting of a crowd of bright umbrellas heading off into the distance. She cheated the vanishing point by making the people vanish into a funky blue fog as they were on the verge of being vanished by a mathematical formula.

I turn from that to a painting by my father, where two Spanish widows step gingerly down the stairs towards us, turning their back on the vanishing point and teasing us into forgetting it.

Maybe the best thing about infinity is that we always think we can capture it, or if not that, beat it or best it, and we keep trying. The number of ways to do so appears to be –

You guessed it.

Animal neighbors, Saint-Prex

And the wind blew harder still! When the cold and wild bise winds blow across the plain to whip up Lake Geneva in Switzerland, thoughts turn to warm coats. I found these creatures dressed for the weather.

When the cold and wild bise winds blow across the plain to whip up Lake Geneva in Switzerland, thoughts turn to warm coats. I found these creatures dressed for the weather.

'Twas a blustery kind of day

And the wind blew and blew and blew!

Saint-Prex, 22 November 2005

In the nearby fields it blew this way and that . . .

The fishermen's flag fought to stay straight, even as the day drew to a close.

Tuesday, November 22, 2005

Monday, November 21, 2005

The country house guest

Charolais country, Burgundy - France

Charolais country, Burgundy - FranceCountry homes in Burgundy are meant to be shared, for the pleasure of all.

They are places of repose and rejuvenation, where wining and dining are the centerpieces of each day and conversation is a brook traveling over smooth stones, rough mossy patches and sudden exhilerating little waterfalls.

They are places of repose and rejuvenation, where wining and dining are the centerpieces of each day and conversation is a brook traveling over smooth stones, rough mossy patches and sudden exhilerating little waterfalls. The Burgundian country home guest has responsibilities: bring news of friends and family, allow yourself - however briefly - to be part of the intimate landscape of the home and the communal one of the lanes and fields and villages that wrap around you.

The Burgundian country home guest has responsibilities: bring news of friends and family, allow yourself - however briefly - to be part of the intimate landscape of the home and the communal one of the lanes and fields and villages that wrap around you. It is November, the land outside is wet and cold, with white frost hovering over everything, beast or plant or other. Animals push out rods of white steam with each breath. The fields have lost their careless appearance and are now drawn starkly with green borders and white centers. The landscape has reinvented itself, an inspiration to the rest of us. In the kitchen we study the last harvest, two ripe tomatoes and two green that might yet redden in the window, a pinch of rosemary found in a hidden corner the sun reaches.

It is November, the land outside is wet and cold, with white frost hovering over everything, beast or plant or other. Animals push out rods of white steam with each breath. The fields have lost their careless appearance and are now drawn starkly with green borders and white centers. The landscape has reinvented itself, an inspiration to the rest of us. In the kitchen we study the last harvest, two ripe tomatoes and two green that might yet redden in the window, a pinch of rosemary found in a hidden corner the sun reaches.Saturday evening. We sit around the blazing fire, sharing a bottle of Pouilly Fuissé, one of France's finest white wines, from a small vineyard 30 km away. Daniel, who makes this and the Beaujolais Village (aged, not the young wine) we drink later, has become a friend. We pass the platter of pâté en croûte, the name to which no translation can do justice: meat and pastry sounds edible, but not exquisite, which the French implies.

It is the season for game and mushrooms and nuts, all of which find their way to the stuffings bowls at the local butcher shop.

It is the season for game and mushrooms and nuts, all of which find their way to the stuffings bowls at the local butcher shop. We step down into the cozy dining room and sit at a table set for four, under an old candelabra that hangs from the ceiling: another one of Evelyn's brocante (some say antique dealer, some say junkman) under-€3 finds, lovingly restored. We talk about the sad state of Beaujolais vineyards, many of which are being snapped up by the British, dreaming of country homes with wine bottles growing off the vines. If the European Union survives it may well owe something to this old love affair of the British for French cultural traditions. The French sit back amused, watching the price of property climb, or at least those French whose cashflow problems have not yet cut into the economics of Sunday dinner.

We step down into the cozy dining room and sit at a table set for four, under an old candelabra that hangs from the ceiling: another one of Evelyn's brocante (some say antique dealer, some say junkman) under-€3 finds, lovingly restored. We talk about the sad state of Beaujolais vineyards, many of which are being snapped up by the British, dreaming of country homes with wine bottles growing off the vines. If the European Union survives it may well owe something to this old love affair of the British for French cultural traditions. The French sit back amused, watching the price of property climb, or at least those French whose cashflow problems have not yet cut into the economics of Sunday dinner.Saturday night menu:

green beans with guinea fowl livers

Charolais lamb braised in Cognac, with celeriac pureé

cheese, with 12 year old port served in a fine glass decanter with the curves of a swan, but the weight of a bull

a bite of chocolate from the local patissier

The pause

bread pudding, made with Italian panetone

Sunday morning. Lost in fog again. Three of us drive in the blind car to Charolles, feeling our way past two castles and a bridge that sits silent, beautiful and mostly unnoticed in this corner of Burgundy that deserves more tourists. We are in search of morning croissants to go with the foaming hot milk and coffee that Evelyn prepares in our absence. Three old men laugh about their PMU (betting) results and tug at their caps to keep out the cold. Two young men, confident they will never be bald, rush by and tug at jacket zippers to pull collars closer to bald heads. A child watches in fear from a safe distance as two men fuel the fire on which the chestnuts will be roasted later: this is the annual chestnut festival in Charolles. A young woman who stayed out too late last night stops to let an elderly widow pass before her, into the butcher's shop.

Sunday morning. Lost in fog again. Three of us drive in the blind car to Charolles, feeling our way past two castles and a bridge that sits silent, beautiful and mostly unnoticed in this corner of Burgundy that deserves more tourists. We are in search of morning croissants to go with the foaming hot milk and coffee that Evelyn prepares in our absence. Three old men laugh about their PMU (betting) results and tug at their caps to keep out the cold. Two young men, confident they will never be bald, rush by and tug at jacket zippers to pull collars closer to bald heads. A child watches in fear from a safe distance as two men fuel the fire on which the chestnuts will be roasted later: this is the annual chestnut festival in Charolles. A young woman who stayed out too late last night stops to let an elderly widow pass before her, into the butcher's shop. The butcher is proud of his meat, justifiably, says David. The former butcher was number one in France, he says, and I wonder how this is measured. The young man who took over not so long ago is also excellent. The French are particular about their food and love to debate what makes a perfect cut of meat. Judging by the crowd in this tiny shop, the new butcher has proven worthy.

The butcher is proud of his meat, justifiably, says David. The former butcher was number one in France, he says, and I wonder how this is measured. The young man who took over not so long ago is also excellent. The French are particular about their food and love to debate what makes a perfect cut of meat. Judging by the crowd in this tiny shop, the new butcher has proven worthy.Later, the croissant crumbs cleaned away and Martha's jam back in the cupboard, we decide to walk. But first we hold Martha's jam up to the light, for the sun has suddenly pushed its way through the fog. This, then, must be how the first cathedral builders chose to add stained glass windows, to leave worshippers in awe that such colors could stand still. Martha, the widow of a diplomat, is known for her charitable works and her magnificent cooking. We praise the quince jelly and fig jam, both from her garden fruit. Evelyn makes us long to become artisanal chefs when she described how Martha makes geranium and rose petal jellies, beautiful to behold, better yet to taste.

I wonder if my crazy mountain-climbing nasturtiums could be turned into jelly, a lovely bright orange. David thinks so, but suggests I crystalize them first. This is beginning to sound like one of the many romantic projects I will undertake in my eighties, when I finally have time.

We walk to the next village, where Evelyn's daughter and friend have just bought a house. It needs work, but it is good to see that the dream of the country house is alive and well: the British house in Burgundy, with a particularly strong Scottish streak.

The garden is across the path and as I peer at the plants left by the old people who lived a long and quiet life here, I see the magic of next year's perfect garden in the seeds, still hanging, before winter triumphs over these last stalks. "Yes, I think she's taken a fancy to gardening," I hear Evelyn say as she peers at some strawberry shoots.

The garden is across the path and as I peer at the plants left by the old people who lived a long and quiet life here, I see the magic of next year's perfect garden in the seeds, still hanging, before winter triumphs over these last stalks. "Yes, I think she's taken a fancy to gardening," I hear Evelyn say as she peers at some strawberry shoots.

It often begins that way.

We guests must always remember to sign the guest book, under the beautiful lamp that Eveyln made, to help us, and their daughter's haunting painting.

The next morning the sun came out and the children made the first snowballs of the season.

The next morning the sun came out and the children made the first snowballs of the season.